The Moon Is Not What You Think: Buzz Aldrin’s Quiet Revelation and the New Age of Looking Up

When Buzz Aldrin’s voice thins and his eyes gloss at the word “Moon,” people sometimes mistake the moment for fragility. It is not. It’s a pressure wave from 1969 still moving through him—what he once named, with the economy of an engineer and the precision of a poet, “magnificent desolation.” If you listen closely, the emotion doesn’t say mystery or confession. It says meaning. Aldrin’s trembling isn’t the tremor of doubt; it’s the aftershock of understanding.

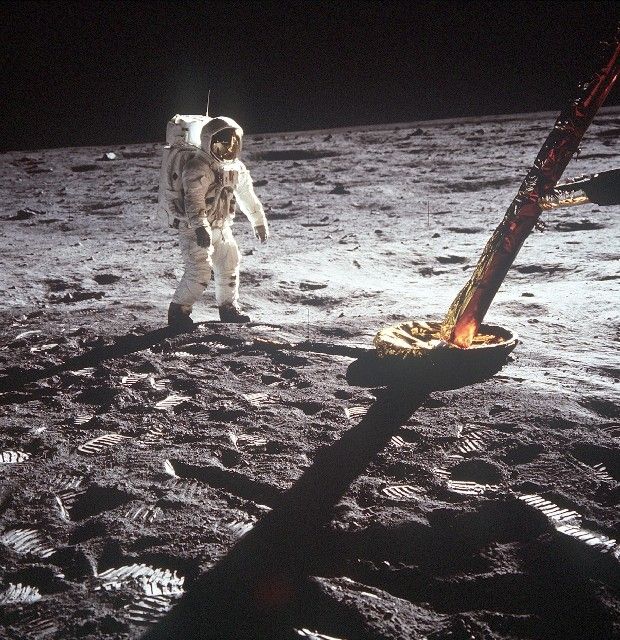

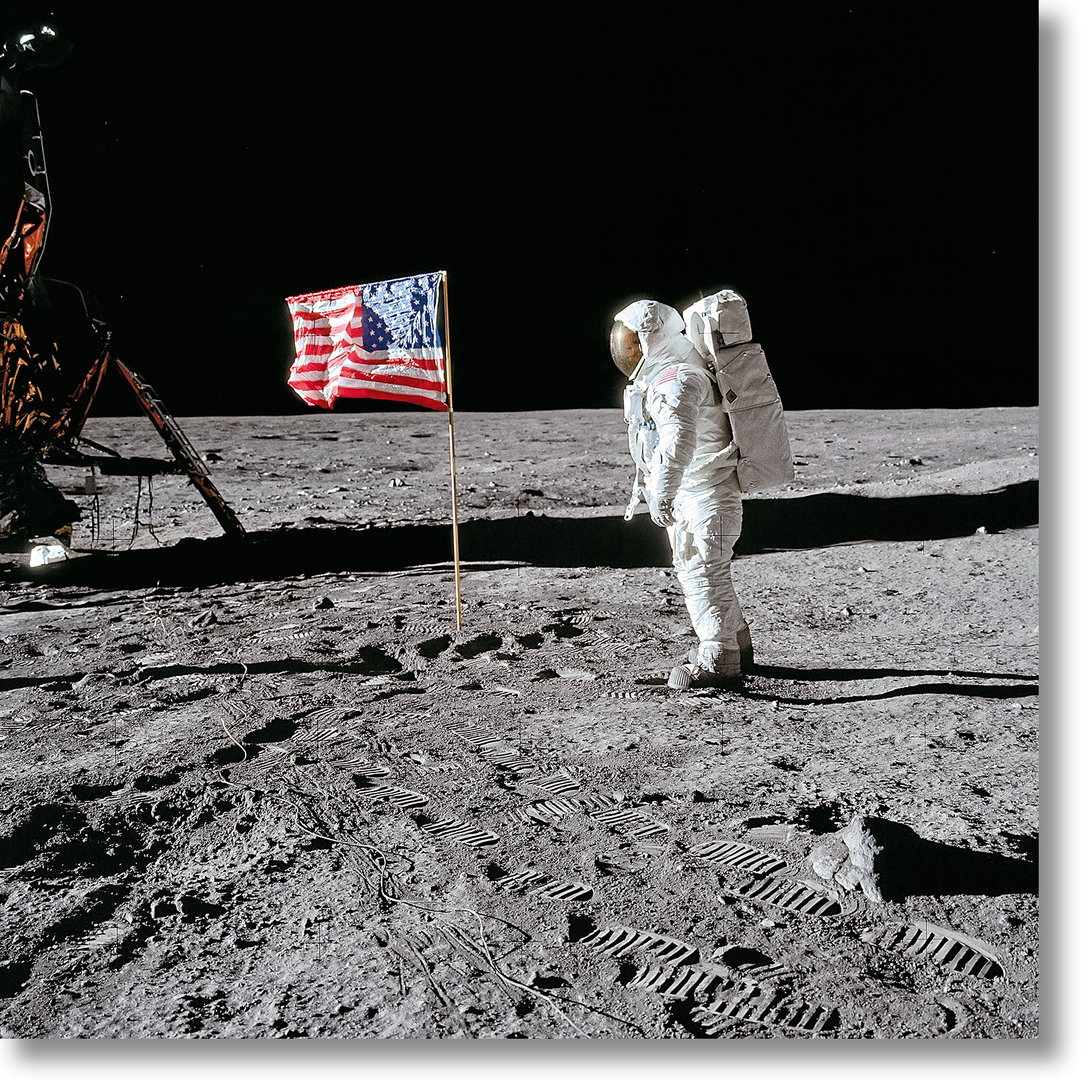

For half a century we have repeated the easy part of the story: the launch, the landing, the flag against a sky so black it swallows stars. We show the grainy footage, lace it with trumpet music, and call it victory. But victory was only the surface. What lingered, for the men who stood where no human had stood, was a paradox: you leave the Earth to understand the Earth. You step onto another world to learn how to live on your own.

Aldrin’s sentence—“The Moon is not what you think”—sounds like a riddle. It isn’t. It’s a calibration. It’s the second man on the Moon reminding us that the place you imagined in lullabies and film reels is not the place where dust clings to your suit like time, where a footstep can last longer than a civilization, where silence isn’t a pause between sounds but the absence of sound itself.

And yet, as algorithms comb craters and neural networks parse shadows in eternal night, his words feel less like nostalgia and more like instruction. Maybe we didn’t know the Moon at all. Maybe we still don’t.

The Weight That Followed Him Home

Watch Aldrin in interviews across the decades—CBS, GQ, People—and you see a pattern. He can slip into the quick cadence of the fighter pilot and mission specialist—checklists, delta-v, rendezvous windows—then, without warning, soften into something else. That something else arrives when he talks about looking back: Earth small and blue, set into a black so absolute it feels solid.

“It’s beautiful,” he says, and the word falters. Beauty is the shallow word we use when we’ve run out of better ones. What he means is fragile. What he means is far. What he means is home.

During the Apollo 11 anniversary, an interviewer asked the most obvious question: What moment stays with you? Aldrin said, barely above a whisper: “The silence.” No wind. No birds. No air to carry sound at all. Our planet is a constant orchestra—weather, leaves, the low astonished moan of cities. The Moon is a theater after the audience is gone, a stage light burning in emptiness. If it looks serene on screen, understand: serenity is what humans project on places that do not care. The Moon is indifferent. In that indifference, Aldrin found perspective.

That perspective didn’t evaporate at splashdown. It rode home with him, clinging tighter than lunar dust. He has spoken honestly about the hard years that followed—public adoration outside, private weather within. The Moon had given him a peak no ordinary day could match. Yet the thing that bruised wasn’t the drop from triumph; it was the clarity. Once you have looked at your home from a quarter million miles away, the traffic light is still a traffic light—but it flickers inside the knowledge that everything in its glow is contingent. It is hard to come back to grocery stores after infinity.

So when Aldrin says, “The Moon is not what you think,” hear the man who learned the limits of triumph. The Moon was not a trophy. It was a teacher.

The Mission Before the Meaning

Aldrin was not sent to be a mystic. He was sent because he was a ruthless, disciplined problem-solver—Air Force fighter pilot, MIT doctorate, the first astronaut with a Ph.D. His specialization—orbital rendezvous mechanics—sounds antiseptic and is in fact the fragile miracle that made lunar docking possible. “Dr. Rendezvous,” they called him. Precision was his element.

Apollo 11’s descent turned precision into survival. When computer alarms flashed, Armstrong took manual control of Eagle while Aldrin called out velocities and fuel numbers in a steady drumbeat, anchoring the chaos. The line that changed history—“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”—was followed, on Aldrin’s loop, by a low, controlled exhale and two words: “Beautiful view.” The view mattered—but so did the composure. History was written by hands that didn’t shake.

Before those hands pressed into the dust, Aldrin performed a ritual you won’t see on posters: alone in the lunar module, he took communion from a small kit he had brought with permission. A private act, neither spectacle nor sermon. Later he described it as gratitude. He had not gone to the Moon to plant a doctrine; he had gone to give thanks for a seat at reality’s edge.

Outside, the famous hours begin: the flag, the core samples, the seismometer, the slow antigravity ballet. But the photographs can’t transmit what the suits contained—the vertigo of a horizon that curves closer than it should, the way shadows carve into black knives because there is no air to soften them, the way walking becomes choreography because your body’s rules are rewritten.

This is the part triumph leaves out: success was work. Beauty arrived as a side effect—like frost on a window after you’ve spent all night fixing the furnace.

Magnificent Desolation

We keep circling Aldrin’s phrase because it still refuses to resolve into a single meaning. Magnificent is our human shout; desolation is the universe’s reply. One without the other is sentimental. Together they cancel and complete.

To stand in that desolation is to feel two truths at once:

Your species is capable of impossible things.

Your species is small.

You are a brief arrangement of atoms aching for significance. You are also proof that the universe can look at itself and say I am.

From that paradox, Aldrin’s tears make sense. He does not weep because the Moon is strange. He weeps because the Moon is honest. It does not pretend to be hospitable; it does not apologize for silence. It receives the flag without joy or malice. It gives you back yourself—scaled to the right size.

No textbook has a chapter on what to do with that.

When the Machines Began to See

Fifty years later, a different kind of gaze has joined Aldrin’s: machine eyes. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter sweeps like a patient brush, and deep-learning models turn its images into elevation maps so detailed we can read the history of impacts like Braille. AI finds cold traps in craters never touched by sun—pockets where water ice can sleep for eons. Neural networks reprocess Apollo seismography and whisper: the Moon’s core may not be the dead cinder we imagined.

Japan’s SLIM lands with algorithmic grace, India’s Chandrayaan-3 plants a soft foot at the south pole, autonomous decisions blinking through dust the way a heart finds rhythm in a new body. The Moon that once answered only to rockets now yields to pattern recognition. Where Aldrin found awe by breath, AI finds signal by statistics. These are not opposites. They are lenses.

Aldrin would not have resented the lenses. He argued for Mars before it was fashionable again, for building pathways that outlive the men who sketch them. The machines can get us there, he said, but they can’t feel what it means to arrive. The work before us is not to pick between feeling and finding; it is to braid them so tightly that the rope holds when gravity tugs.

Consider the volcanic glass beads scattered across plains like dark punctuation. AI-assisted spectrometry tells us those beads cradle molecules of water, archives of geologic breathing. Consider reinterpreted Moonquakes that hint at molten trace beneath crust. The gray isn’t as empty as we said. The Moon remains a record we’re just now learning to read—the palimpsest of our solar system’s adolescence, scribbled over but not erased.

Aldrin’s sentence—“not what you think”—applies again. The Moon keeps editing our assumptions.

What Silence Teaches

The lunar void is not merely a lack of sound; it is a mirror for attention. On Earth, background noise sands down our anxieties; it gives us permission to be distracted. On the Moon, attention has nowhere to hide. That is part of the weight Aldrin talks about when his voice trembles: the way a place can force you into presence. Every motion becomes deliberate not only because survival demands it, but because meaning does.

In that attention, something else becomes visible: home as an object, not a habitat. To see Earth small is not to diminish it; it’s to frame it. The borders vanish from that frame. The arguments sound like insects at a cathedral door. The atmosphere glittering like a sliver suddenly looks, in a word that should terrify us into tenderness, thin.

The Moon taught Aldrin—and through him, us—that exploration is not conquest. It is consent to be changed.

The Man Who Returned and the Question He Carried

Aldrin came back with two biographies, the public one and the private one. The public man shook hands at parades. The private man wrestled with the same thing all returned travelers wrestle with: how to live at ordinary scale after the aperture has been blown wide.

He did the brave thing and spoke about it. About the depression, the drift, the slow work of rebuilding a life that was no longer a countdown but a clock. In that candor is another kind of exploration. He made it possible for future astronauts—and future anyones—to admit that awe can leave a tenderness that needs tending. You don’t return from “magnificent desolation” and fall back into small talk unscathed.

If there is a quiet heroism in Aldrin’s later years, it is that he kept showing up: to museums, to classrooms, to microphones he didn’t always want to face. He kept telling the truth that we went as technicians and came back as witnesses. He kept repeating that the Moon isn’t a postcard from a past triumph—it’s a syllabus for the future.

Artemis, and the Risk of Forgetting What Matters

We are going back. The Artemis program’s architecture reads like a symphony of acronyms; the mission patches glow with promised horizons. Cargo and crew, Gateway and lander, south pole and sunless ice. The logistics are thrilling, the engineering pure poetry.

And yet: the danger in sophisticated returns is amnesia. We could let autonomy do so much that we forget to assign meaning. We could turn the Moon into a gas station on the way to Mars and skip the chapel on the hill.

The fix is not to romanticize more. It is to remember what Aldrin learned: measure and marvel. Put philosophers on flight manifestos—not as payload, but as purpose. Train crews not only in checklists and geology but in the ethics of presence, the stewardship of footprints, the stewardship of wonder. Teach every algorithm to whisper a human question to its operators: What will this change in you?

If we return merely to extract, we will have missed the point of having gone at all.

Machine Vision, Human Meaning

There is a temptation to pit AI’s cold clarity against a veteran’s warm tears. That is a false duel. When machine learning discovers water beads in basalt, it is not replacing Aldrin’s awe; it is providing it with a vocabulary. When a neural net maps a crater’s shadow for trapped ice, it is not subtracting a heartbeat; it is extending it across light-years of data.

The Moon doesn’t need our warmth. We do. AI can tell us where to land and what to drill and how to manufacture oxygen from regolith. It cannot kneel in a small metal cabin with a thimble of wine and whisper thank you. It cannot feel the sickening sweetness of seeing your world as a world for the first time.

So the compact should be clear: let the machines make us capable of leaving home again. Let humans make us worthy of it.

Why He Cried

It is easy to mythologize a moment of tears and make it carry more than it can. Aldrin’s emotion doesn’t need embellishment. It needs companionship.

He cried because the Moon stripped the narrative down to what withstands vacuum: the fact of being alive against odds so long they stop having meaning. He cried because the silence was not empty; it was accurate. He cried because triumph, untempered by tenderness, becomes noise—and he had heard a place where noise cannot live.

Mostly, though, he cried because the Moon made Earth visible in the way a mirror makes a face visible—not as an emblem, but as a fact. We are small. We are luminous. We are temporary. We are capable of climbing ladders into darkness and returning with light.

“The Moon is not what you think,” he said. He meant: let it change what you think.

The Next Sentence in a Very Long Story

If Aldrin was the witness of first arrival, AI is the apprentice scribe of second sight. Together they move us from romance to relationship. The Moon of ballads becomes the Moon of baselines; the Moon of algorithms becomes the Moon of awe, again.

We will send robots into the night markets of crater floors to shop for ice. We will print bricks from dust. We will test suits and habitats and the hard limits of psychology. We will argue, because we are human, and pause mid-argument when Earth rises, because we are human.

And somewhere on a future live stream—high resolution, cooled sensors, telemetry projected in translucent ribbon—there will be a quiet human voice saying a line that doesn’t trend but endures: It’s not what you think. The sentence will be less about the rock and more about the eyes.

When explorers stand again on that “magnificent desolation,” they will carry Aldrin’s insight like a second oxygen supply. When machine eyes map the last unlit inches of the last unnamed pit, they will sip from Aldrin’s cup whether they know it or not.

Because the point of exploration is not to make the unknown behave. It is to let the unknown correct us.

A Closing for Those Who Look Up

You do not need a rocket to practice what the Moon taught. Tonight, go outside. Find the bright coin above your roofline. Remember that it is not glowing; it is remembering sunlight. Remember that its dust still holds footprints because nothing there erases them. Remember that on that dust a man once whispered thanks. Remember that the silence he found is not there to frighten you. It is there to tune you.

Buzz Aldrin’s tears were not an ending. They were a calibration mark on our species’ long instrument—a note you set your ear by before you sing. As AI and rockets and programs with mythic names take us outward, keep that note.

Because the Moon isn’t what you think— and that is the best reason to go back.

News

🎄 Lakers Owner SHOCKS the World as LeBron’s NBA Deal CRASHES — The Truth Behind His Christmas Betrayal Revealed! 👇

Lakers Owner EXPOSES LeBron’s Plan — NBA MASSIVE DEAL COLLAPSED! The truth has just been exposed, and it’s nothing short…

🎄 LeBron James Left Stunned as Netflix Pulls the Plug on His Biggest Basketball Dream — Christmas Bombshell! 👇

LeBron James HUMILIATED As Netflix DESTROYS His Biggest Basketball Project! In a stunning blow to LeBron James and his business…

NBA Stunned After What LeBron Said About Charles Barkley On Live TV!

NBA Stunned After What LeBron Said About Charles Barkley On Live TV! The NBA world froze in disbelief when LeBron…

🎃 BREAKING NEW: Lakers Owner PAYING LeBron $40M To LEAVE — ‘We Don’t Want Him Back!’

BREAKING NEWS: Lakers Owner PAYING LeBron $40M To LEAVE — ‘We Don’t Want Him Back!’ In a shocking turn of…

🎃 SHOCKING: Lakers Owners KICKED OUT LeBron After PED Allegations EXPOSED — DEA Documents Surface!

SHOCKING: Lakers Owners KICKED OUT LeBron After PED Allegations EXPOSED — DEA Documents Surface! In an earth-shattering revelation, LeBron James…

BREAKING: Austin Reeves HUMILIATES LeBron’s Legacy — ‘You DESTROYED My Game For 5 Years!’

BREAKING: Austin Reeves HUMILIATES LeBron’s Legacy — ‘You DESTROYED My Game For 5 Years!’ In a stunning turn of events,…

End of content

No more pages to load